Today’s question of the day comes from Sue K. in Dallas (emphasis mine) –

…a friend told me her trainer insists that all of her exercise be tracked by METs, and that if anyone doesn’t do it that way, they’re framing their entire approach to exercise wrong. When I asked her to define for me what a MET actually was, she wasn’t sure, but said they were something related to units of exercise. I’m just coming back to the workout and exercise game after 20 years of sedentary life, have things changed and I’ve totally missed out on something here?…

Sue, in a nutshell, of course the answer is no, you don’t have to frame your thinking about exercise around the concept of METs to “do it the right way”. METs do have their place in describing physical activity; for instance, you may see METs listed on various pieces of exercise equipment in a gym, though as described, the trainer’s admonition doesn’t hold water.

So Just What is a MET?

A bit of background is in order here. We all understand that muscle cells consume oxygen as they generate the energy to contract, more calories are burned as you burn more oxygen (we as humans burn approximately 5 calories of energy to consume 1 liter of oxygen).

One MET is defined as the amount of oxygen consumed while at rest; it’s roughly 3.5 ml of O2 per kg of body weight, per minute. METs are measures of metabolic cost, and have been tabulated as the ratio of metabolic rate (expressed as the rate of energy consumption) against a given physical activity – for example, walking, running, resistance exercise, housework, they’ve even calculated the METs required for sex.

More practically, one MET is for practical purposes the amount of energy produced relative to your body mass at rest; reading this blurb on your computer requires one MET of energy at rest.

The Master MET List: The Compendium of Physical Activity

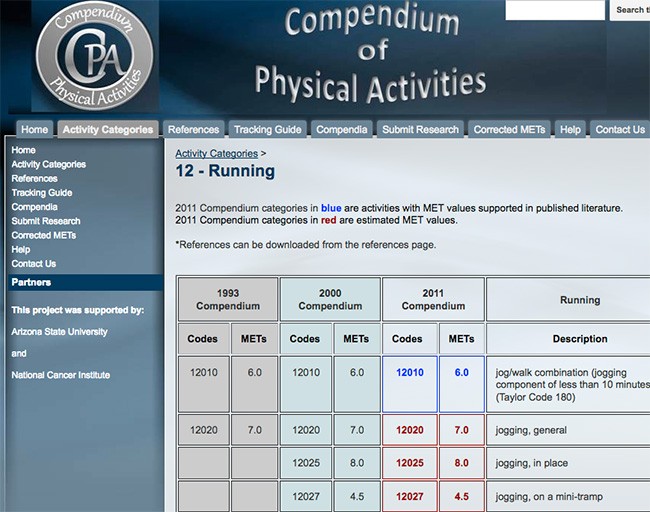

The powers that be have compiled a fairly comprehensive list of the METs required to complete a host of different physical activities – it’s posted in The Compendium of Physical Activity, most recently updated in 2011. There are several apps that list the various MET values for different activities as well.

Here’s a sample list from the Compendium –

METs and Exercise for Most of Us

In defense of the (reported) trainer’s comment above, you could reasonably argue that if you know the particular MET value for a given physical activity, how long that activity is performed, and some basic metrics about the person performing the activity, you can estimate the caloric burn (consumption) that person should experience as a result.

That said, while I used the concept of METs in roughly developing rehabilitation plans for severely compromised patients (strokes, massive cardiac events, brain injuries, etc.), I’ve never framed exercise goals in terms of METs for anyone at anytime otherwise.

Why not? There are a host of reasons, though most importantly two in particular.

One, the concept of using METs to track exercise often tends to be framed in the context of “calories in, calories out” (and its kissing cousin – “a calorie is a calorie is a calorie”), which as we now understand, particularly in the context of someone above their ideal body weight and metabolically compromised, probably doesn’t hold water and can lead one down the wrong path.

And two, for most of us, tracking METs, really tracking your METs for both exercise and all activities during a given day, can end up being a handful (to say the least), and can smack of (at least in some contexts) compulsive behaviors and orthorexia. It’s critical to remember that for almost everyone, your food plan determines 80% of your body composition, with exercise (again, for most of us) impacting roughly 10%.

Your approach to activity simply doesn’t have to be that complicated; move, move, move (at aerobic levels of exertion) + lift heavy things occasionally + sprint now and again wins the day for just about everyone.

Now and again we get a hankering for a great quiche, though like many of you, we stopped cooking traditionally-crusted quiches at home several years as we became more Primally/Paleo aligned with our nutrition plan.

Now and again we get a hankering for a great quiche, though like many of you, we stopped cooking traditionally-crusted quiches at home several years as we became more Primally/Paleo aligned with our nutrition plan. Combine the crust ingredients and pat into 2 deep 9-inch pie plates; we find the crust releases easier if you lightly coat the plates first with either avocado or extra virgin olive oil. Bake the crusts for 20-30 minutes until the sweet potatoes begin to brown. Remove from oven and set aside.

Combine the crust ingredients and pat into 2 deep 9-inch pie plates; we find the crust releases easier if you lightly coat the plates first with either avocado or extra virgin olive oil. Bake the crusts for 20-30 minutes until the sweet potatoes begin to brown. Remove from oven and set aside. Once again, for the most part, I’m pleased as punch overall after spending now slightly over eight months in nutritional ketosis, though for at least two weeks (one over the holidays), I’m sure I was drifting in and out of NK during the week.

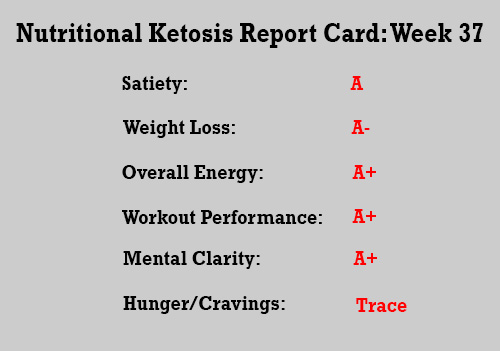

Once again, for the most part, I’m pleased as punch overall after spending now slightly over eight months in nutritional ketosis, though for at least two weeks (one over the holidays), I’m sure I was drifting in and out of NK during the week.